Why Jalaur may not be enough.

| Highlights: • The water supply problem in Iloilo is not new but circumstances may have changed as a result of the rapid pace of economic growth. • We have estimated water demand as 250 million liters per day (MLD) for the Metro Iloilo District (MIWD). The actual supply deficit may be close to 185 MLD in the MIWD service area • It is estimated that only about 29% of households in the water district have connections • The Jalaur River Project and the Metro Pacific Desalination Plant project will likely not be able to eliminate the shortage leaving a still significant deficit • Iloilo ranks 8th among provinces in having the highest water tariffs in the country • Other complementary supply sourcing and demand reduction efforts must be explored and acted on now |

The more things change, the more they seem to stay the same

Back in 2010, I wrote a piece with the same title as this article. That article stemmed from a study written by a consulting firm engaged by the World Bank to undertake a study of the water situation in Iloilo. Muddling the waters (pun intended) was the then acrimonious bickering between the Board of Directors of the Metro Iloilo Water District (MIWD) and its Management. Amidst allegations of incompetence and corruption, the underlying problem of inadequate water supply and distribution was shunted aside. It would take at least a decade before the recommendation of the World Bank-commissioned study of a PPP arrangement saw the light of day.

Just a little over 5 years ago, the MIWD and Metro Pacific Water signed a joint venture agreement to form Metro Pacific Iloilo Water (MPIW). MPIW commenced operations in July 2019 taking over the provision of water distribution and sanitation services for a concession area which covered Iloilo City and the municipalities of Oton, Sta. Barbara, Cabatuan, Maasin, San Miguel, Pavia, and Leganes.

Demand and Supply

As with many of our previous research efforts, the availability of available and usable data to determine the demand and supply situation for human water consumption is a challenge. Nevertheless, we believe we have been able to put together a reasonable database to support some realistic conclusions. The first conclusion is simple enough, the MIWD concession area is and has been in a water supply deficit situation. This brings up the question, by how much?

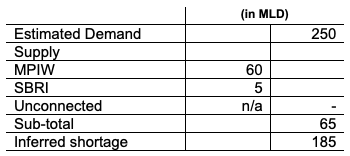

The Institute estimates that water demand for Iloilo City and the municipalities covered by MIWD is 250 million liters per day (MLD). We estimate that between MPIW and South Balibago Resources, Inc. (SBRI) supply provided to their subscribers is about 65 MLD. At first glance, the water supply shortage amounts to 185 MLD per day but it’s not that simple.

Only 29% of households have connections

MPIW and SBRI only have connections to 29% of the 201,000 households in the concession area. This totals about 58.500 households which have water connections with either MPIW or SBRI. So, the other 142,500 households are getting their water supplies from other sources whether in full or in part. It may also be that they don’t have access to water at all.

The impact of Non-Revenue Water loss

Simply put, non-revenue water (NRW) loss is water that does not make it from point A (the source of the water distribution system) to point B (the end user) due to leakage, wastage, or theft. These losses can be real, physical losses (caused by leaks, breaks, spills, etc.) or only apparent losses that occur as a result of broken or tampered meters, poor meter reading, inaccurate record keeping, or outright water theft.

When MPIW started operations, NRW was 50%. They have since reduced this to 40%. This means that of the 60 MLD that they are distributing to their consumers, only about 36 MLD actually reaches these consumers.

The table below summarizes the discussion on demand and supply so far.

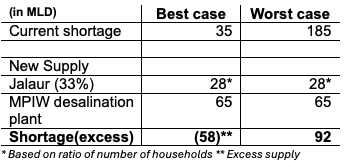

Supply shortfall between 35 to 185 MLD

The key unknown is the amount of water that the unconnected households need and use. There is just no way of knowing due to the absence of data nor the ability to track usage.

There are two extremes, one is that they don’t have water at all which means that our shortage is really 185 MLD. The other extreme is that they are getting all the water they need from some source in which case the shortage in supply is only 35 MLD which is the shortfall of the existing consumers with water connections. The reality will be somewhere between the two extremes. We would surmise that the number is closer to 185 than it is to 35.

The promise of Jalaur

The Jalaur River Multipurpose Project Stage II is expected to produce 86 MLD of bulk water supply. We have to remember, however, that this has to be shared with the 20 other water districts in the Province which need to serve just over 300,000 households themselves.

Another supply source in the pipeline is the 65 MLD Desalination Facility which MPIW is in the process of awarding to a contractor.

All of that leaves us with this:

A real threat to the economy and human well-being

The numbers that we have come so far do not factor in growth in demand. If Iloilo is to attract new investment to further stimulate economic growth, the problem of water scarcity will need to be resolved. It is highly probable that demand for water will grow. This is especially true in an environment where water use intensity increases with industry-led growth.

Of equal, if not more, importance is that the lack of access to safe water is a threat to human health and well-being. Access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene is the most basic human need for health and well-being.

Impact on affordability

Data provided by the Local Water Utilities Administration show as of December 31, 2023, water districts in Iloilo average the 8th highest (among 76) water tariffs in the country. On average, we pay P24.51 per cubic meter (on the first 10 cubic meters). The national average is P20.65/cu m while the median tariff rate is P20.33/ cu m in Northern Samar.

Planning ahead

The controversial Elon Musk caused a stir in the water world last year when in an interview with Bill Maher he said, “desalination is absurdly cheap,”. Musk was basically argued that water supply in the world can be sustainable through desalination. In the current environment, we point out that while indeed, the cost of desalination has gone down significantly, it is still beyond the reach of many developing countries. Still, as an example the Sarek Desalination Plant in Israel provides water at a cost of US$0.45/cu m or roughly P25. It is expected that the technology cost could further 20% in the next 10 years or so making it comparable to our current tariff regime.

The keys are to promote desalination in conjunction with renewable energy and to be mindful of the prospective threat to marine life and its ecosystem. Energy costs are one of the biggest cost components of desalination and need to be tempered by access to renewable energy sources for its operation.

In the short to medium term, this may be the most impactful solution to Iloilo’s water supply problem. To be relevant, however, we need to attract investment to build another desalination plant with a similar capacity as the one being built by MPIW.

Alternative, complementary solutions

Beyond desalination, we need to expand efforts promoting better water use. These alternatives include:

Rainwater Harvesting

Rainwater harvesting involves collecting and storing rainwater for non-potable uses such as flushing toilets, washing cars, and irrigating plants. This alternative reduces the demand on potable water sources and can help mitigate the effects of droughts.

Grey Water Systems

Grey water systems collect and treat wastewater from sinks, showers, and washing machines for irrigation and flushing toilets. This alternative reduces the amount of wastewater sent to treatment plants and conserves potable water.

Brackish Water Treatment

Brackish water is a mixture of fresh and saltwater that can be found in estuaries, mangroves, and coastal areas. Treating brackish water can provide a reliable source of fresh water, especially in areas where desalination is not feasible.

Water Recycling

Water recycling, also known as wastewater reuse, involves treating wastewater to make it safe for drinking, industrial use, or irrigation. This alternative reduces the demand on potable water sources and can help alleviate water scarcity.

Fog Collection

Fog collection involves using mesh nets or other materials to collect fog droplets, which can provide a reliable source of fresh water in coastal areas.

Atmospheric Water Generation

Atmospheric water generation involves using heat and humidity to extract water from the air, making it possible to produce fresh water in areas with high humidity.

Aquifer Recharge

Aquifer recharge involves injecting treated wastewater or stormwater into underground aquifers to replenish the water table and provide a sustainable source of fresh water.

Water Conservation

Water conservation involves reducing water consumption through efficient appliances, fixtures, and practices. This alternative is essential for reducing the demand on water resources and conserving this precious resource.

These are just some alternatives and/or complementary solutions to desalination that can provide a reliable and sustainable source of fresh water. By adopting these alternatives, we can reduce our reliance on desalination and mitigate the environmental and social impacts associated with it.

We need to explore and make a concerted effort to promote and actualize these solutions. Education and incentives are required to build these solutions into practice.

La Niña

The forthcoming La Niña weather phenomenon may offer some reprieve but only that – a reprieve. It will likely bring up the volume of water supplied to the level prior to El Niño, 70-75 MLD (from the current 60 MLD). Furthermore, the impact will not be immediate. Water turbidity will initially increase causing difficulties in processing raw water into potable water flowing through distribution pipes to households.

Final thoughts

There are some other items which the various stakeholders can do and/or explore in the meantime:

- Fix supply imbalance

SBRI has the capacity to receive more water than it requires. This is estimated to be at least 2 MLD. It seems that MPIW and SBRI cannot agree on commercial terms for SBRI to sell this excess to MPIW. It would be good for government to mediate between the two parties for the sake of the community that will serve to benefit from the additional water supply.

- Fast-tracking NRW loss reduction

When MPIW took over the management of water distribution from MIWD, NRW in the system was at 50%. Over the past 5 years, MPIW has been able to bring it down to 40% with an aim to bringing it further down to 35% by 2030 as called for in their concession agreement. Fast tracking investment into NRW-reduction measures adds about 3 to 4 MLD of water supply reaching consumers’ households.

- Revisit separation of water supply and water distribution

Two years prior to the awarding of the water distribution concession to MPIW, Metro Pacific Water and MIWD entered into a joint venture agreement for the provision of bulk treated water to then MIWD, now MPIW. It may have been easier at that time to separate the functions of MIWD and enter into agreements with private sector partners in this manner. However, it may now be time to explore combining these functions again into one entity to focus efforts on the end goal of water utility services which is to serve the water needs of consumers. Distribution requires sourcing supplies for distribution. Putting these under one entity is likely to lead to better efficiencies, lower over-all costs for water services, and a singular interest in the provision of water to consumers. This will also motivate the surviving entity to be more aggressive in seeking alternative sources of water vis-à-vis the current separated structure. We face a challenging next few years staring at a real water crisis. We need to realize that this will be a recurring and institutionalized hardship on our people unless we are able, as a community, to work together in acting on solutions now.