A look at the complex ecosystem in the battle for the business of Iloilo City’s water supply.

REPORT OVERVIEW AND SUMMARY

The report discusses the challenges and developments in the water supply system of Iloilo City, focusing on governance, water distribution, and the performance of private water utilities.

Historical Context of Water Supply in Iloilo

The water supply system in Iloilo City has a long and complex history, marked by various administrative changes and challenges. The system was established in 1926 and has undergone multiple transitions, leading to current issues in water sourcing and distribution.

- The Iloilo waterworks system was established in 1926 under Commonwealth Act No. 3222.

- NAWASA was created in 1955 to centralize waterworks control, later replaced by MWSS in 1971.

- In 1978, MIWD took over operations, which continued until a joint venture with MetroPac Water in 2016 and another joint venture establishing Metro Pacific Iloilo Water (MPIW).

- The current structure separates water production from distribution, complicating supply issues.

Current Water Supply and Demand Issues

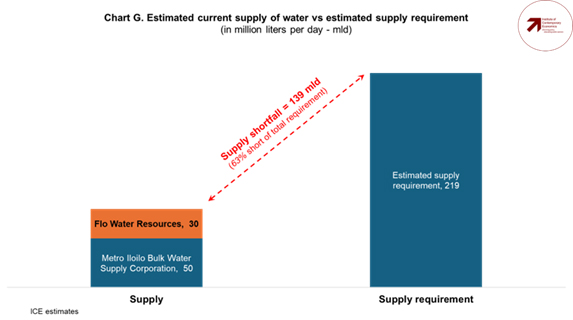

Iloilo City faces significant challenges in meeting its water supply needs, with a substantial gap between demand and available supply. The current sourcing methods are insufficient to meet the growing needs of the population.

- Current water supply sources include surface water, groundwater, and by 2027, a new desalination plant.

- MPIW is only able to source 60 to 80 million liters per day (mld).

- The Metro Iloilo Bulk Water Supply Corporation appears to be capable of delivering 30 to 50 mld, far below the 170 mld initially promised.

- Estimated domestic water demand is 153 mld, requiring a total supply of 219 mld when accounting for 30% non-revenue water (NRW).

- The supply shortfall is approximately 139 mld, or 63% of the required amount.

Performance Comparison of Water Utilities

A comparative analysis of Metro Pacific Iloilo Water (MPIW) and Laguna Water reveals significant differences in performance metrics, particularly in connection growth and NRW reduction. These metrics highlight the challenges faced by MPIW in expanding its service during the pandemic.

- Laguna Water increased connections by 272.4% in its first five years, while MPIW only achieved 12.1%.

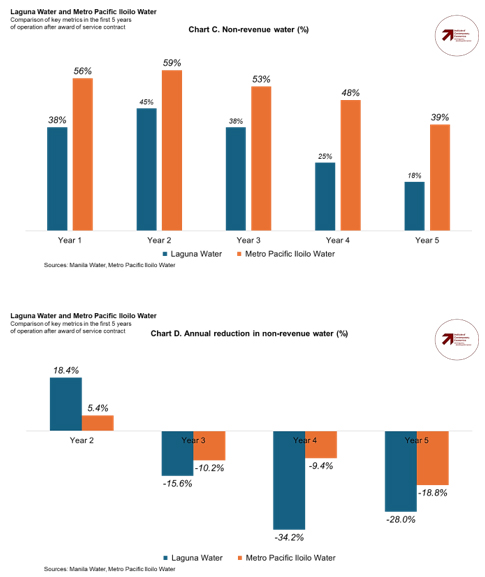

- MPIW’s NRW decreased from 56% in 2019 to 39% in 2024, still significantly worse than industry peer averages.

- MPIW’s coverage rate is only 26%, leaving 74% of households without access to its services.

Regulatory Environment and Water Pricing

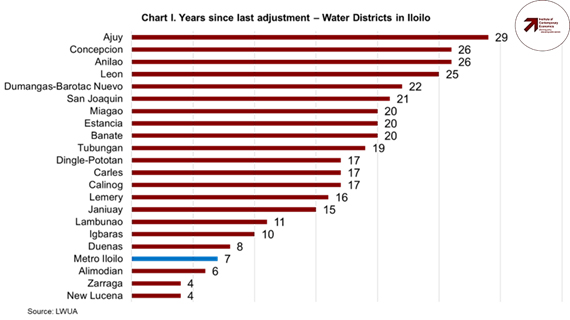

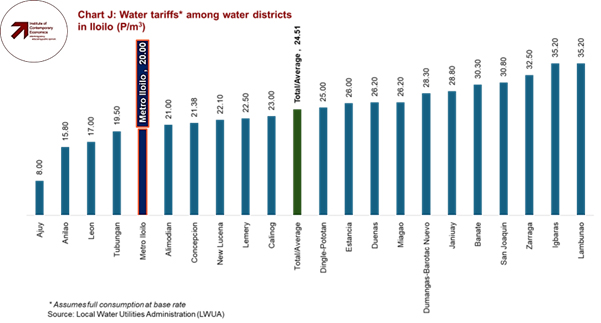

The regulatory framework governing water pricing in the Philippines is outdated and has contributed to the financial struggles of water districts. The need for higher tariffs is emphasized to ensure sustainable water supply and infrastructure.

- Water tariffs are regulated by LWUA, but many districts have not adjusted rates in over 5 years.

- The average water price in Iloilo is P24.51 per cubic meter, significantly lower than the global average of P124.23.

- Aboitiz InfraCapital’s proposed rate of P40 per cubic meter is deemed reasonable given the context of water scarcity.

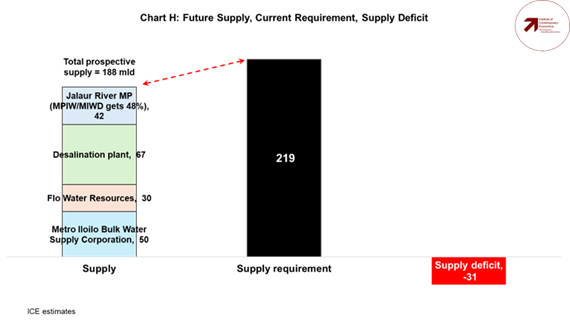

Future Water Supply Developments

New water supply projects, including the Jalaur Multipurpose Project and a desalination plant, are expected to improve the water situation in Iloilo City. However, allocation issues may arise due to competing demands from other districts.

- The desalination plant is projected to deliver 66.5 mld by 2027.

- The Jalaur Multipurpose Project is expected to produce 86.4 mld within two years.

- Allocation estimates suggest MIWD/MPIW may receive 42 mld from JRMP, still leaving a supply gap.

Long-Term Water Management Challenges

The historical neglect of water resource management in Iloilo has led to significant environmental and infrastructural challenges. Urgent action is needed to address these issues and ensure sustainable water access for the future.

- Groundwater management plans have been delayed, exacerbating resource depletion.

- The need for regular monitoring and updated data on water resources is critical.

- Without intervention, the risk of running out of water remains a pressing concern.

HOW WE GOT HERE

Since time immemorial, the supply of water provided by the water distribution utility for consumer use has been a problem for Iloilo City. The waterworks system for Iloilo City was first established in 1926 when Commonwealth Act No. 3222 authorized the Provincial Government of Iloilo to issue bonds to fund the establishment of a waterworks system. In other words, the province was authorized to borrow money to build the system. The system was completed in 1928 and was run by the province until 1955 through the Iloilo Metropolitan Waterworks.

In 1955, the national government decided to consolidate and centralize control of all the waterworks systems in the country. Thus, was created the National Waterworks and Sewerage Authority better known as NAWASA. Many have traced the decline of the water system in Iloilo City to the latter years of the NAWASA administration.

After 15 years, NAWASA was abolished and was replace by the Metropolitan Waterworks and Sewerage System or MWSS. MWSS ran the city’s waterworks from 1971 to 1978. Two years after the takeover of MWSS, Presidential Decree No. 198 was promulgated creating the Local Water Utilities Administration (LWUA) as well as authorizing the formation of local water districts.

In 1978, LWUA turned over the city’s waterworks operations to the Iloilo City government which simultaneously delegated this to the Metro Iloilo Water District (MIWD).

Until 2016, the sourcing and distribution of water was under one entity. This changed when MIWD entered into a joint venture (JV) project with MetroPac Water Investments Corporation (MPW) for bulk water supply. MIWD and MPW incorporated the Metro Iloilo Bulk Water Supply Corporation (MIBWSC), as the JV company which would undertake the activities in accordance with the Joint Venture Agreement. This had the effect of separating the production and supply of water from the distribution component which remained with MIWD.

Then in 2018, MIWD entered into another Joint Venture Agreement with Metro Pacific Water (MPW) providing for a 25-year concession for the rehabilitation, expansion, and improvement of the water distribution system and wastewater management facilities of MIWD. This eventually led to the formation of Metro Pacific Iloilo Water (MPIW) which began commercial operations in 2019.

UNFULFILLED PROMISES?

Bulk water supply

Our water supply currently comes from two sources, surface water (e.g. rivers, lakes) and groundwater produced from wells. The desalination plant being built by Metro Pacific Water will add a third component to our sources of water.

In the agreement between MPW and MIWD, the bulk water joint venture company, MIBWSC, is supposed to provide 170 million liters of water (mld) for the needs of the concession area of MPIW including Iloilo City. It would appear, however, that this has not been the case. This has necessitated an additional supply agreement with FloWater Resources for 30 mld of bulk water.

Reports are that MPIW is only able to source 60 to 80 mld to provide for its customers. LWUA numbers show that the MIWD produced 2,506,326 cubic meters per month in 2024 which translates to roughly 82 mld. This would mean that MIBSWC is only able to provide between 30 to 50 mld of water, a significantly lower amount than the 170 mld promised in its agreement with MIWD. It may well be that MIBWSC will be able to provide this amount by the end of its agreement, but the need is now, and it may well be difficult to identify other sources of developable water in the province of Iloilo to procure this water.

This may be the very source of the brewing fight between the Metro Pacific group and Aboitiz InfraCapital. We will return to this later.

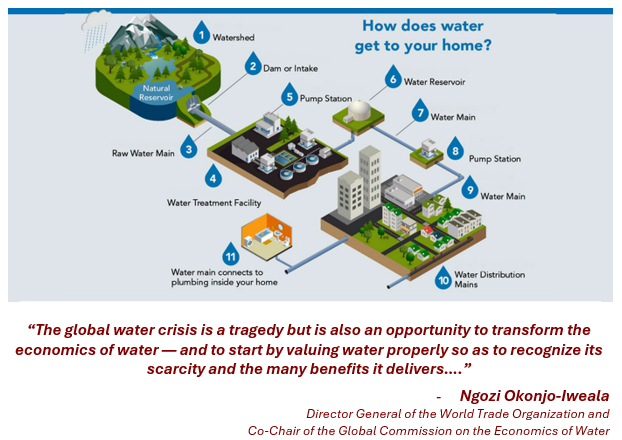

Water distribution

The provision of water for industrial and consumer use comprises an ecosystem which includes the sourcing and distribution of the commodity. In the Philippine setting, this ecosystem is characterized by a regulated distribution system and a sourcing environment which includes an unregulated bulk water market pricing mechanism. The National Water Resources Board (NWRB), has however, passed a resolution last year initiating the regulation of bulk water pricing. The Implementing Rules and Regulations were supposed to have come out in late March, but none has so far been released to the public.

We would be remiss if we did not also review the performance of our current water distribution utility and its role in the supply of water to our community. With that in mind, part of our analysis is a peer comparison between Metro Pacific Iloilo Water and Laguna Water. The choice of Laguna Water is based on demographic considerations and the type of commercial or legal engagement governing their agreements with their respective water districts or local government unit. In this case, both companies have service contract agreements with water districts in their respective area of coverage.

While it is almost impossible to control for all variables in producing perfectly identical peers, the similarities between the two companies carry enough weight to make key metric comparisons in terms of the improvements in the number of connections, reduction in Non-Revenue Water (NRW) and coverage.

Our analysis covers the first 5 years of operation of these private water distribution utilities.

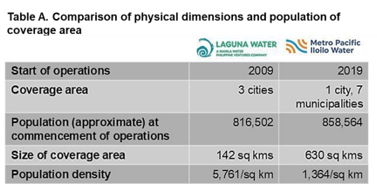

Coverage area

To come as close to a peer-to-peer comparison, we looked at the coverage area of the two entities looking at the geographic size and an approximation of their populations during the first 5 years of their operations. Having started in 2009, the population estimated for Laguna Water is the 2010 Philippine census while that for Metro Pacific Iloilo Water is the 2020 Philippine census. Table A shows these comparisons.

The population sizes are roughly similar at the commencement of each entities’ operations. The geographic size of MPIW is significantly larger at 630 sq kms compared to 142 sq kms for Laguna Water. Population density, on the other hand, skews heavily in favor of Laguna Water with a population density of 5,761 per square km whereas it is 1,364 per sq km for MPIW’s coverage area. We argue, however, that since a substantial majority of MPIW’s coverage area is Iloilo City, metric comparisons between the two would still be valid. The 78.34 sq km that comprises Iloilo City yields a population density of 5,842 sq km almost similar to the Laguna Water coverage area density of 5,761.

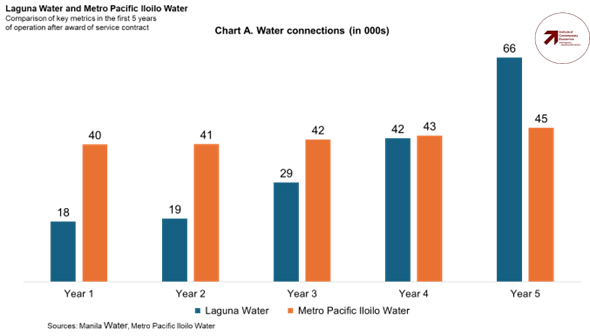

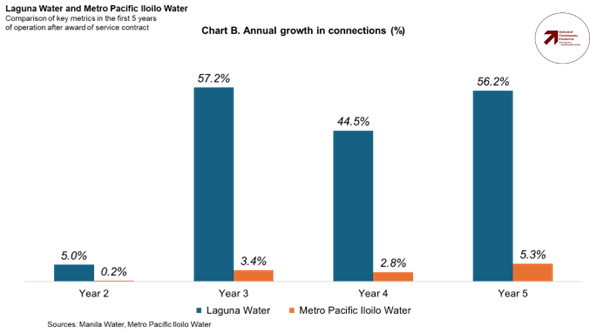

Connections

The difference in the number of new connections is quite stark. During its first five years of operations, Laguna Water has increased the number of connections in its coverage area by 272.4% compared to only 12.1% for MPIW. We do have to consider that the first 3 years of MPIW’s operations was severely affected by pandemic-related restrictions. Be that as it may, even in 2024, MPIW was only able to install 2,271 new connections in a coverage area which has approximately 200,000 households needing to be served. In terms of growth in new connections, MPIW has shown single-digit annual growth in its first 5 years of operations whereas that of Laguna Water has reached as high as 57.6%.

Non-revenue water

Non-revenue water (NRW) is water that has been produced but does not reach customers and other end users. and is “lost” before it reaches the customer. In technical terms, the International Water Association’s (IWA) definition of NRW is the difference between the cubic meters of water that are distributed into the water distribution network and the cubic meters that are invoiced with the customer. NRW includes real losses (physical losses, such as leakages), apparent losses (commercial losses, such as illegal water connections) and unbilled authorized consumption (such as water used by fire fighters, or for the watering of public parks).

The main implication of NRW, in practical terms, is that any new supply of water will not be maximized if the leakages contributing to NRW are not fixed.

MPIW has been able to reduce NRW in its coverage area from 56% in 2019 to 39% in 2024. This is a significant reduction that will benefit consumers in terms of water actually flowing out of their faucets. There remains a lot to be done but this has been a major area of improvement relating to MPIW’s operations. An NRW of 39% is, however, still far from industry averages which can range from the high single digits to the low teens. As an example, Laguna Water was able to reduce NRW to 18% by the end of the fifth year of their concession agreement.

Percentage of coverage

MPIW attained coverage of 26% at the end of 2024. This means that there are still 74 out of every 100 households in its concession area that do not have access to water provided by MPIW. This really quite low and unacceptable for a highly urbanized city and its metro area. This is a major area of concern particularly since the increase in coverage was basically unchanged between 2023 and 2024.

In the context of the controversy in sourcing additional water, equal attention should be given to the relatively disappointing performance of MPIW. From both an absolute and relative standpoint, the water distribution utility should be asked to do more.

More transparency required particularly from MIWD

As a publicly owned entity operating as a Government Owned and Operated Corporation (GOCC), MIWD should be more proactive and transparent in disclosing the progress (or lack thereof) in meeting the milestones of the joint venture engagements that they have entered into.

LOOKING FORWARD

Water demand and the supply-demand gap

We have focused so far on the supply of water to meet the needs of Iloilo City and the rest of the coverage area of MPIW / MIWD. The question is – how much water do we actually need and how wide is the gap between supply and demand?

The estimation of the domestic use of water is usually done by taking the population of an area and multiplying this by the average consumption of water per person per day. Then, an estimate of commercial and industrial demand is added on top of this to get the total demand.

The difficult part is estimating the average consumption per person per day. A lot of factors such as the state of the water system as well as the economic status of a particular region play into this. The range of average consumption per person can be as low as the 21 liters per person per day in Senegal to as high as 380 liters per person per day in the UAE. For purposes of our analysis, we used a base assumption of 150 liters per day.

The resulting figure would be that our demand for domestic water would be 153 mld. Factoring in a rate of 30% for NRW, Iloilo City and the other areas covered would need to have a supply of 219 mld to meet demand. This means that the supply shortfall is 139 mld or about 63% of what is required.

It is likely that the actual supply required (i.e. demand) is actually higher than what we show. Our estimates are based on the 2020 Philippine census and population growth will have driven demand higher.

Future supply

There are two new sources of water supply that are being developed. The first is the Jalaur River Multipurpose Project (JRMP) and the second is the previously mentioned desalination plant. The desalination plant is projected to deliver 66.5 mld of water by 2027. The JRMP, on the other hand is expected to produce 86.4 mld at some point within the next two years. It is safe to assumed that all of the production of the desalination plant will go the MPIW / MIWD. The question of the allocation of the JRMP water remains unanswered. What many people are not aware of is that there are 21 other water districts in the province. They will also be lobbying for their share of water for domestic use from the JRMP.

If we assume that the allocation is based on demand, our estimate is that MIWD/MPIW will get 48% of the JRMP water production or 42 mld. This will bring the supply of water to MPIW to 188 mld, still 31 mld below what the estimated demand is for the total number of households in their coverage area. If the allocation were to be based on population, however, MIWA/MPIW is looking at receiving only 34% of water production coming from the JRMP. Nevertheless, this influx of supply will have a significant positive impact on existing consumers of MPIW. The problem will lie as actual demand rises with the increase in the number of connections over time.

THE PRICE OF WATER

The regulatory and industry management environment

Water tariffs (or the price of water) are regulated by the LWUA. In theory, the prices are determined by the LWUA by considering the following factors:

- cost of systems expansion

- operation and maintenance cost

- number of connectors

- debt service needs of the water district

- ten percent reserves

- operating efficiency

The regulation of water utilities is quite ancient. The governing law remains the 52-year-old Presidential Decree No 198 or the Provincial Water Utilities Act of 1973. The various amendments via two subsequent presidential decrees and one Republic Act (No. 9286 which basically just amended the compensation of the directors of water districts and amended the manner of appointment of the General Manager of Water Districts) are by themselves ancient or not substantive. On top of these are changes or new regulatory mandates from Letters of Instruction, Executive Orders, IRRs, court decisions, memorandum circulars and other similar instruments.

This only highlights the need to replace and consolidate PD 198 and other subsequent issuances with new legislation. The regulatory environment that has existed after all these has been an unsustainable industry marked by derelict water and sewerage systems, financially insolvent or essentially bankrupt water districts and a weak accountability and oversight regime.

Another layer of complexity is added with the authority to appoint members of the Board of Directors of the water district delegated to provincial governors and mayors of cities and municipalities. This has led to an insufficiently equipped boards who are unable to handle technical and financial matters related to water distribution and oversee water district operations.

Financial (mis)management of water districts leading to deteriorating infrastructure and collapse of service delivery

Water districts are allowed to apply for a revision of water tariffs every five years. The LWUA Water Rates manual explicitly specifies the need for the adjustment of water rates. Section 7 of the manual states:

“In the establishment of water rates, specifically in making projections, allowances for escalation of cost in relation to power, fuel, labor, and even foreign exchange are integral components. There are, however, some instances when abrupt increases in cost of these items are incurred and are not covered by these allowances for escalation, the experience of which might result to losses in operations. In such cases, adjustment of rates becomes necessary which should be considered as interim measure until the next water-rate increase where its effects can be reflected in the cashflow projection…”

The insufficient level of expertise at the water district level can best be seen in the number of years since the last tariff adjustment among the 22 water districts in Iloilo. On average, these water districts have not seen an adjustment in 16 years. Only 2 of the 22 water districts in Iloilo have received an approval for increases in the last 5 years.

The most glaring example of this has been the water district of Ajuy which has not implemented an increase in 29 years. It is inconceivable to think that LWUA, for all its shortcomings, would not grant even one tariff adjustment over a period of 29 years. The question lies with the Board and the Management of these water districts – do they even file an application for an increase in tariff rates over all these years?

The failure to enact a water tariff increase has resulted in wildly uneconomical tariff rates which do not reflect the reality of current costs. It is not then, a surprise that service delivery to consumers of many of our water districts has collapsed. In the case of the Ajuy Water District, they currently have a minimum charge of P80 per consumer or a rate of P8 per cubic meter assuming consumption of 10 cubic meters for a month. This water district only has 313 connections as per the latest data from LWUA. This translates to a coverage rate of just over 2% for a concession area that includes about 13,000 households.

The 2022-23 Audit Report of the Ajuy Water District includes the following among its audit findings and observations:

“The District had been operating at an average annual loss of ₱103,271.98, from 2014 to 2023, inconsistent with the characteristic of a CPSE, as contemplated under COA Circular No. 2015-003, thereby resulting in the accumulation of unpaid salaries and benefits amounting to ₱2.705 million and unremitted mandatory deductions / contributions of ₱2.307 million, as of December 31, 2023, limiting the District’s growth and development.

We recommended and Management agreed to develop and implement business and operating strategies, which include the campaign for additional service connections, an action plan to minimize the NRW, and undertake necessary steps in the request for an increase in water rates, notwithstanding the ongoing development projects and improvements.

We also recommended and Management agreed to make representation and partner with the Local Government Unit, and LWUA for funding or financial assistance and work on improvements and development projects to further improve the water supply systems and overall operations, which would translate into a better financial performance.”

To survive, it received a cash infusion of P4.9 million from the National Government in 2023.

While we cite the specific case of the Ajuy Water District, it is nothing more than an emblem of the deplorable state of water distribution in the Philippines and the overwhelming majority of its water districts.

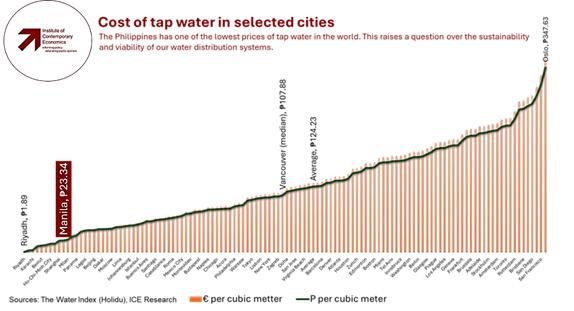

THE NEED TO ACCEPT HIGHER WATER RATES

The viability of our waterworks systems requires that we begin to accept the need for higher water tariffs. We have already seen what an uneconomical tariff environment has wrought in terms of the deterioration of our water supply infrastructure and indeed, the collapse of service delivery.

The Philippines has one of the lowest water tariffs in the worldThe Philippines already has one of the lowest water prices in the world. In a survey of 120 cities, the Water Index shows that the average price of tap water translates to about P124.23 per cubic meter. Manila’s price in the survey is P23.34, the average for the 22 water districts in Iloilo is P24.51 per cubic meter while MPIW charges an implied tariff P20.00 per cubic meter with full utilization at the minimum charge.

In this context, the price being offered by Aboitiz InfraCapital of P40.00 per cubic meter is more than reasonable.

There is also, however, the urgent requirement that LWUA open its eyes to the changed world of water access marked by resource scarcity as a result of the growing impact of climate change. It must pivot to accepting, reviewing and approving applications for water tariff adjustments quickly.

LWUA shoulders a significant amount of responsibility for the virtual collapse of our water districts. Its utter failure to fulfill the purpose of its charter directly and unequivocally attest to its culpability. Section 50 of the Local Water Utilities Administration Law states that:

“The Administration shall primarily be a specialized lending institution for the promotion, development and financing of local water utilities. In the implementation of its functions, the Administration shall, among others: (1) prescribe minimum standards and regulations in order to assure acceptable standards of construction materials and supplies, maintenance, operation, personnel training, accounting and fiscal practices for local water utilities; (2) furnish technical assistance and personnel training programs for local water utilities; (3) monitor and evaluate local water standards; and (4) effect system integration, joint investment and operation, district annexation and de-annexation whenever economically warranted.”

Water is underpriced

Global Water Intelligence in its 2024 Global Water Tariff Survey cited a “…broader trend worldwide of rising water tariffs influenced by a ‘perfect storm’ of rising costs, overdue upgrades, infrastructure expansions and investments in resilience to climate change.” Beyond this, there has been a systematic underpricing of water as a resource. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, director general of the World Trade Organization and a co-chair of the Global Commission on the Economics of Water, said in the statement that “(T)he global water crisis is a tragedy but is also an opportunity to transform the economics of water — and to start by valuing water properly so as to recognize its scarcity and the many benefits it delivers…”. The underpricing of water and engenders wasteful use and inhibits the urgent need to be serious about conservation measures for this growingly scarce resource.

We cited earlier a decision by the NWRB to regulate the price of bulk water. While we understand the rationale of the decision, this may well be a step in the wrong direction. A balance has to be struck between keeping water as affordable as possible with the realization that water as resource needs to be valued realistically. This will be a complicated balancing act which may require a policy direction to be decided at higher levels.

In most other resource markets, the market itself determines the price of a resource, a familiar example of which, are oil prices (subject to OPEC-driven supply interventions). The world will soon realize, if it hasn’t already so, and begin to accept the need for a commodity market for water. Water can no longer be seen as a free resource where the determination of its price is largely dictated by the costs related to its extraction and distribution. Given its necessity as a basic human need, government, as a matter of policy, will have to decide whether to let market forces allow water to seek its natural pricing level given demand and supply considerations and have consumers bear the full cost of market prices or allow such to still happen but subsidize the price at which consumers pay for it.

The alternative scenario

Preserving the status quo whether it be in water pricing or the current usage patterns is a recipe for disaster. It consigns our people to buying commercial water in the form of bottled water whose costs can be as much as thousands of pesos per cubic meter or from water trucks where prices range from P150 to P250 per cubic meter. When compared side by side, P40 per cubic meter is a no-brainer. Even when topped off by a distribution utility’s pricing mechanism, the resulting rate would still be considered reasonable.

The status quo also forces the continued extraction of groundwater. This risks exacerbating the attendant damage that this does to our environment such as through saltwater intrusion and land subsidence – damage which we know has already happened and continues to progressively get worse.

A long history of neglect

The problem we have with our water supply has had a long history as we had earlier alluded to. This was formally acknowledged by the government in the NWRB’s Water Resources Management Plan released in 1998. In that report, Metro Iloilo was identified as a highly urbanized water constraint area. It identified the need for “…the preparation of a Groundwater Management Plan for Iloilo City and its surrounding areas, as a strategy in groundwater utilization, allocation, protection and conservation”.

It would take another 15 years or until 2013 for this report – GROUNDWATER MANAGEMENT PLAN: Development of Groundwater Management Plan for Highly Urbanized Water Constraint Cities (Pilot Area: Iloilo City and Surrounding Areas of Oton, Pavia and Leganes) – to come out. This report highlighted the continued damage done to our groundwater ecosystems citing the following as reasons:

- Weak implementation of existing strategies and policies on ground water management such as the rules and regulations spelled out in the Water Code;

- Outdated and incomplete hydrogeological databasing, specifically on aquifer parameters and groundwater information system;

- Unregulated utilization of groundwater, particularly for domestic (households), commercial water delivery and industrial uses;

- Intrusion of seawater as observed in the coastal areas of Iloilo City, Leganes and Oton;

- Absence of regular monitoring of groundwater withdrawal, water level and quality;

- Lack of enabling environment, such as local legislation adopting the Water Code of the Philippines and Clean Water Act to support groundwater management;

- Poor assessment, planning and management of groundwater resources;

- Lack of technologies to enhance storage capacity of groundwater reservoirs;

- Inadequate personnel capacity and resources to fulfill the mandatory groundwater resource management function;

- Lack of a communication plan focusing on promoting “best practices” on groundwater use and management; and

- Absence of harmonization of an integrated water resources management approach and climate change adaptation to groundwater resource planning for sustainable infrastructure (climate proofing).

Among the supposed measures to be taken as contained in this management plan was the “(U)pdating of groundwater and surface water database…” via quarterly reports. This is critical to monitoring the amount of water withdrawals that we make to ensure we are not using more than what can be replenished. Without this, we may just wake up one day to find out that we have run out of water. The Institute has since filed a Freedom of Information request to the NWRB for this data to which we have so far not gotten a response.

The price we have to pay

While we have pointed out the need for improvements from our water distribution utility in the form of delivery efficiencies and coverage expansion, when all is said and done, much of our issues stems from the availability of the resource, water, itself. Our collective neglect and failure to act in recognizing that the supply of life-giving water has its boundaries has brought us to this crisis. This becomes even more critical as move into the future.

The need to monitor the rates of water extraction and replenishment, be serious about water conservation and protect our wetlands and coastlines from environmental degradation caused by human intervention has never been more urgent.

In the meantime, we need to accept the fact that we still have water, we just have to pay more for it. P40 is as good as it’s going to get.